Quamash EcoResearch

Ecological research in support of restoration and conservation

Plants, pollinators, and phenology

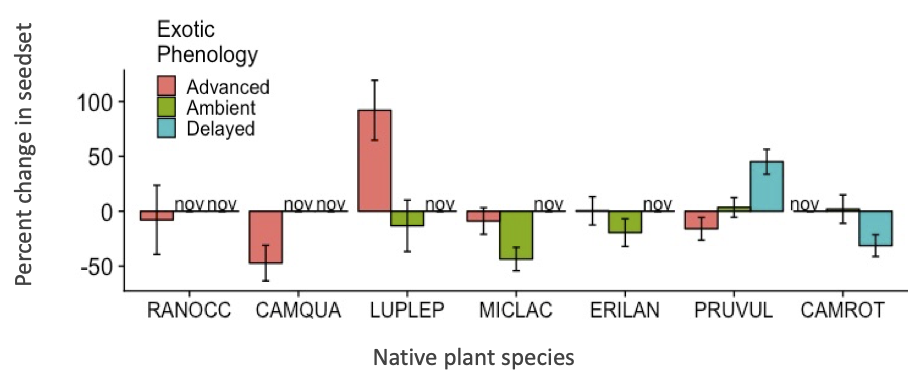

Fig. 1. Seed production by native plant species was altered strongly by changing the flowering phenology of a neighboring exotic plant. Response of native plants (six-letter codes) to a nearby exotic plant (H. radicata) under three treatments manipulating the timing of H. radicata flowering: a) advanced (exotic flowering shifted earlier); b) ambient (timing of exotic flowering not shifted); and c) delayed (exotic flowering shifted later). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals in native seed set. “nov” = no overlap (plants did not co-flower and therefore did not interact).

Thanks to wonderful photographs by David Cappaert, our 2020 paper was on the cover of the Journal of Ecology. Click image for Journal of Ecology's blog about the cover.

Waters, S., Chen, C., and Hille Ris Lambers, J. 2020. Experimental shifts in exotic flowering phenology produce strong indirect effects on native plant reproductive success. Journal of Ecology 00:1-12.

How will a changing climate reorganize plant-pollinator communities? One way is via changing phenologies.

Increasingly, ecologists have recorded changes in organisms’ phenology (timing of life history events, such as flowering) in response to climate change. While many plants are flowering earlier in response to warmer springs, others have delayed or unchanged flowering times. Unequal rates of phenological change can bring about changes in how interacting organisms are aligned in time, altering the duration and strength of their interactions. These changes in synchrony can have surprisingly large demographic effects. To determine how asynchronous phenology shifts might affect plant-plant interactions through shared pollinators, we advanced and delayed the flowering phenology of two common exotic plants, relative to seven native plant species whose phenologies were unmanipulated. We quantified impacts on pollinator visitation and seed set by native plant species relative to an unmanipulated control. Seed production by all natives was strongly and significantly altered, in some cases by more than 50% (Fig. 1).

Our results suggest that individualistic phenological shifts by some plant species have the potential to produce large, unexpected changes in other species’ seed production, with potential future demographic effects.