Quamash EcoResearch

Ecological research in support of restoration and conservation

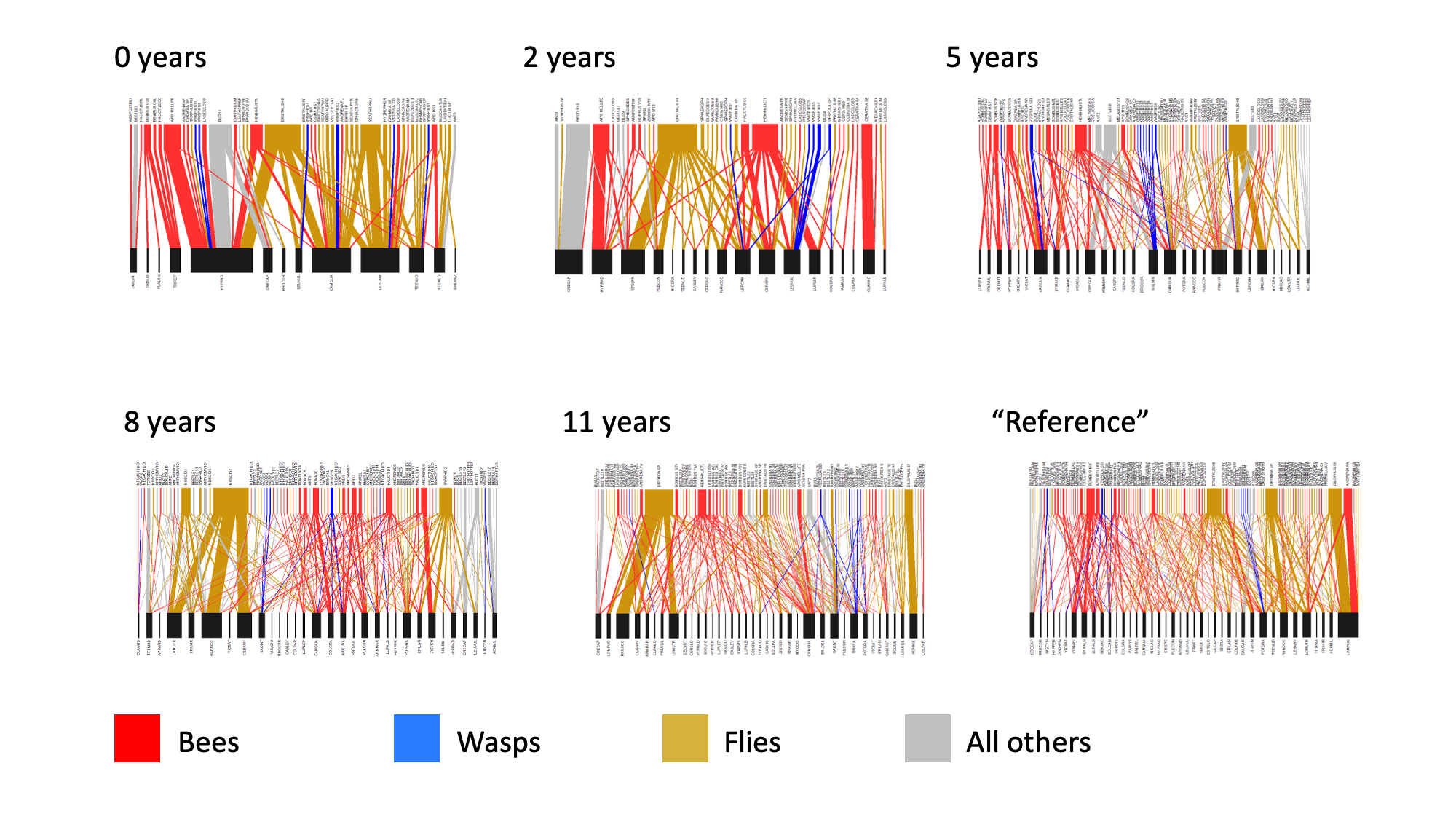

Fig. 1. Complexity increases as restoration progresses. Plant-pollinator interaction networks at Puget Trough prairie sites along a gradient of restoration, from 0 years of restoration to a “reference” site (which has never lost significant native diversity). Bottom axis shows plant species, top axis shows pollinator taxa; connecting lines show an observed interaction in which pollinator contacted flower; line thickness is proportional to interaction frequency.

How do plant-pollinator communities respond to restoration?

Restoration ecology has made tremendous strides in learning to “reset” degraded or invaded sites to native plant-dominated communities, by manipulating disturbance and propagule pressure. However, to sustain such plant-focused restorations, we need to understand how the species that interact with plants respond too. Are we creating communities that reestablish resilient networks of species interactions, or depauperate communities fragile to future change?

Our work tracks changes in plant-pollinator interaction diversity and community structure over the course of restoration time and evaluates network metrics that may be associated with resilience (i.e., maintaining interactions when a species is lost).

To date, our study finds that complexity returns as restoration proceeds (Fig. 1), while network metrics show trends toward values associated with higher resilience.

We also use networks directly in conservation, because they show “invisible” indirect interactions that can affect fitness of key plants or insects of interest. The California bumble bee (Bombus californicus) plays an essential pollinating role for federally threatened golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta; Fig. 2), yet this bee in turn requires floral resources throughout the season to maintain a population that is likely to return the following year. We found that it relied heavily on a plant that has no flowering overlap with C. levisecta, Prunella vulgaris. This suggests that management for rare plants such as C. levisecta may benefit from encouraging apparently unconnected late-season native forbs to support pollination services. Understanding how plants interact indirectly through pollinators is important for conservation.

Network research has been funded by Jim and Birte Falconer, USFWS, USACE, and DoD.

Fig. 2. A California bumble bee (Bombus californicus) visits threatened golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta). The bee requires other floral resources later in the season. Photo: David Cappaert