Quamash EcoResearch

Ecological research in support of restoration and conservation

Ecology of Plant - Pollinator Interactions

Many of our rare Pacific Northwest plants and insects are the focus of intensive conservation efforts, ranging from habitat restoration to captive rearing and planned reintroductions. Yet we often have knowledge gaps about the basic biology of the organism that can slow or compromise these efforts: what eats it? Is it reproducing successfully? Is its population growing or shrinking? We carry out research that helps fill these gaps.

Current Projects

- Western Washington prairies currently cover only 1-3% of their historic range, making prairie restoration essential

- Pollinator populations in the U.S. have also declined rapidly in the last several decades

- Prairie habitat fragmentation provides unique challenges in managing land for conservation of native plants and their pollinators.

- Utilizing private and working lands to enhance habitat connectivity in this matrix will be vital in conserving habitat into perpetuity.

- We aim to promote habitat conservation through collaboration between private landowners, ranchers and restoration practitioners to support enhancement of plant and pollinator diversity.

- Since the project began in 2022, Quamash EcoResearch has conducted repeated pollinator surveys each spring at each of ten properties participating in the project.

- The next phases of the project will continue through 2029, including new site identification, landowner and rancher involvement, and development of conservation grazing plans and targeted implementation of restoration actions.

- Quamash EcoResearch will continue monitoring the plant-pollinator communities at the current and new sites as they emerge.

Past Projects

Restoration ecology has made tremendous strides in learning to “reset” degraded or invaded sites to native plant-dominated communities, by manipulating disturbance and propagule pressure. However, to sustain such plant-focused restorations, we need to understand how the species that interact with plants respond too. Are we creating communities that reestablish resilient networks of species interactions, or depauperate communities fragile to future change?

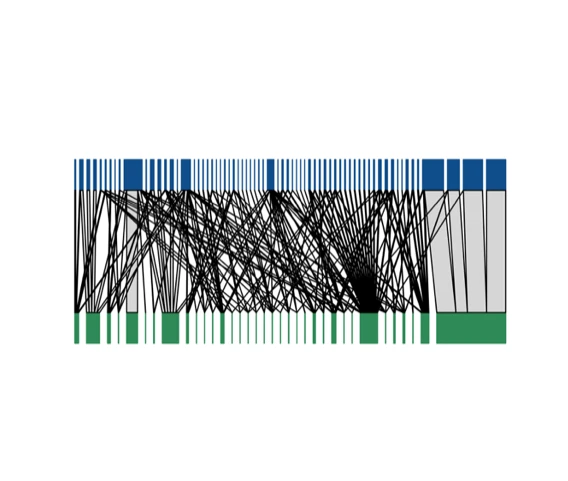

Our work tracks changes in plant-pollinator interaction diversity and community structure over the course of restoration time and evaluates network metrics that may be associated with resilience (i.e., maintaining interactions when a species is lost).

To date, our study finds that complexity returns as restoration proceeds, while network metrics show trends toward values associated with higher resilience.

We also use networks directly in conservation, because they show “invisible” indirect interactions that can affect fitness of key plants or insects of interest. The California bumble bee (Bombus californicus) plays an essential pollinating role for federally threatened golden paintbrush, yet this bee in turn requires floral resources throughout the season to maintain a population that is likely to return the following year. We found that it relied heavily on a plant that has no flowering overlap with C. levisecta, Prunella vulgaris. This suggests that management for rare plants such as C. levisecta may benefit from encouraging apparently unconnected late-season native forbs to support pollination services. Understanding how plants interact indirectly through pollinators is important for conservation.

Network research has been funded by Jim and Birte Falconer, USFWS, USACE, and DoD